Nu på engelsk: Danish municipalities pay millions to Tvind

Nu på engelsk: Danish municipalities pay millions to Tvind

Among the murderers, drug-pushers and kidnappers on Interpol’s list of the 33 most wanted people from Denmark, five members of Tvind’s top leadership can be found. Not because they’ve suddenly resorted to violent crime, but because the five are charged with tax evasion and embezzlement of millions of dollars.

They have been on Interpol’s list for 4 years, ever since the Danish police decided to search for them so that the trial — known in Denmark as Tvindsagen (the Tvind Case) — could proceed as an appeal in district court after the five were acquitted in a city court. Meanwhile, they are imprisoned in absentia.

Nevertheless, Danish municipalities annually pay millions of dollars to Tvind’s social education residences in the country.

“In view of the fact that Tvind leader Mogens Amdi Petersen and four other Tvind people have fled Denmark instead of meeting in court where they are charged with extensive tax fraud and embezzlement, it is in violation of the rule of law that the municipalities continue to support the Tvind empire. One can even imagine that money is being channeled to Amdi’s luxury exile in Mexico. We will not be a laughing stock over how we spend our own tax money.”

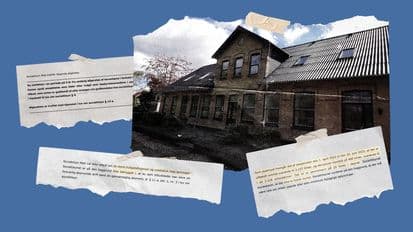

According to documents that kommunen.dk and the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DBC) have been granted access to, Tvind received at least 190 million Danish kroner [US$30 million] from the municipalities in 2016. The amount of money Tvind receives has risen every year since Tvind in the late 1990s converted more of the old boarding schools and folk high schools to take care of socially disadvantaged children and teenagers in the country.

In total, 67 municipalities send children, teenagers and vulnerable adults to Tvind’s group homes and residential treatment schools, kommunen.dk's and the DBC's research shows. That information surprises the chairman of the parliamentary committee, Peter Skaarup (Danish People’s Party).

“In view of the fact that Tvind leader Mogens Amdi Petersen and four other Tvind people have fled Denmark instead of meeting in court where they are charged with extensive tax fraud and embezzlement, it is in violation of the rule of law that the municipalities continue to support the Tvind empire. One can even imagine that money is being channeled to Amdi’s luxury exile in Mexico. We will not be a laughing stock over how we spend our own tax money,” says Skaarup.

Altogether, the residential treatment schools alone received 114 million kroner [$18 million] in 2016, which was used to pay for the placement of at least 235 children. The Tvind institutions that house adult citizens — including young homeless and disabled — received in 2016 at least 18 million kroner [$2.8 million] and 45 people.

The remaining 58 million kroner [$9.1 million], which Tvind collected from Danish municipalities in 2016, was earned by operating folk high schools, special needs schools and several other Danish educational institutions.

'Tvindsagen'

The Tvind Case [known in Denmark as Tvindsagen ] is about whether Tvind’s leadership with founder Mogens Amdi Petersen has committed a tax fraud of 56 million kroner and embezzlement of 52 million kroner.

The case was initiated in 2002 and ended with the acquittal of nearly all the defendants in Ringkøbing City Court in 2006. The prosecutor appealed after 12 days, but by that time most of the defendants had disappeared.

When the appeal case was heard in 2009, Tvind’s spokesman at the time, Poul Jørgensen, was left alone in the dock. He got two and a half years in prison. In 2013, the High Court issued an arrest warrant against the five who were missing from trial, and simultaneously sought them via Interpol. They have since been on Interpol’s list of Denmark’s most wanted.

Most of the wanted have been seen in Mexico and are probably still there, as Denmark has no extradition agreement with that country, which as a rule does not deliver people who have been acquitted by the first court.

From Tvind to Independent

Before kommunen.dk contacted the municipalities, we located the various educational facilities that Tvind manages, by reviewing the website tvindportalen.dk.

The domain name is owned by E-advice, which is located at Skorkærvej 8, [a former farm] in the Danish town of Ulfborg. The same address belongs to the Tvind School Centre and ‘The Necessary Teacher Training College’. Skorkærvej 8 is also the location that gave Tvind its name, as a small stream called Madum Bæk twists its way across the property. [‘twist’ in Old Danish is tvind — pronounced like ‘twin’. ]

When kommunen.dk contacted Tvind for the first time, their website tvindportalen.dk said that it was “the common portal for Tvind’s School Centres.” Under different tabs, the various residential treatment schools, teen boot camps, special needs schools and other programmes were listed.

The Tvind Portal website, as it appeared on 12 Feb 2017, before the kommunen.dk news outlet showed interest in the municipalities’ use of institutions linked to Tvind.

A few days later, however, the website’s wording had changed to state that the website contained “information about a number of residential treatment programmes, group homes and schools that have a community of interest and cooperation around cultural events, exchanging experience and education.”

The Tvind Portal website, as it appeared on 24 April 2017, after kommunen.dk had started investigating the municipalities’ use of Tvind’s places of residence. Later the site disappeared, and the address Tvindportalen.dk now redirects to Tvind.dk.

A week later, the website was closed and redirected to the website of Tvind’s International School Centre, located at Skorkærvej 8 in Ulfborg.

The site has been closed down to avoid misunderstandings, Anders Svensson writes in an email to kommunen.dk — his preferred method of answering our questions. He is head of the school centre, Bustrup, which consists of three residential treatment schools and a day school. He writes that each of the residential treatment schools is autonomous and financially independent, and is organised as a foundation.

He explains:

“The Tvind Portal was written by the Tvind community of interest. The Tvind community of interest is a cultural and educational network. The Tvind community of interest is not a union or organisation, but a non-binding collaboration of educational development, education and cultural interests. The Tvind Portal was closed to avoid misunderstandings.”

The five municipalities with the most placements at Tvind

In 2016, Slagelse Municipality paid 21,918,087 kroner [$3.2 million] for 89 children and young people to be involved in Tvind’s social education programmes. This makes Slagelse the municipality with the largest number of children at Tvind.

Slagelse: 89 children and young people

Aarhus: 34 children and young people

Frederikshavn: 27 children and young people

Skive: 26 children and young people

Aabenraa: 23 children and young people

The five municipalities that spent the most money on Tvind in 2016

Slagelse: 21,918,087 kroner [$3.2 million]

Aarhus: 20,224,837 kroner [$2.9 million]

Vordingborg: 14,773,105 kroner [$2.1 million]

Høje Taastrup: 12,090,269 kroner [$1.8 million]

Odense: 9,817,123 kroner [$1.4 million]

Can you place anywhere else?

Although the information has been made available to the public, no one kommunen.dk has spoken to was aware of the connection between Tvind and the social education programmes.

Former Minister of Social Affairs and current mayor of Elsinor, Benedikte Kiær (Conservative Party) is, like Skaarup, surprised by kommunen.dk's information, which shows that Elsinor’s management has chosen to place children and young people at Tvind’s residences. She will now order an inquiry about whether the municipality can place them elsewhere besides Tvind:

“I actually don’t understand why, when it comes to vulnerable children and young people, one trusts an organisation whose leadership is internationally wanted for tax evasion and embezzlement. Those things do not go well together and I want to investigate whether we have other options in my own municipality — even though the Department of Social Supervision has approved all the places in question,” she says.

In 2016, Elsinor paid about 2 million kroner [$290,000] to Tvind.

In Fredensborg, chairman of the children’s and school committee Hanne Berg (Socialist People’s Party) would want the municipalities to stop using Tvind as well.

“I think it’s horrible and morally problematic. Our taxpayer money is used to pay an organisation that has previously cheated and deceived, and still has pending tax and fraud cases in the US and Brazil,” she says.

Tvind is big

In 2016 1,858 children were placed at residential treatment schools in Denmark. Of these, 235 children — 17.5 percent — were placed at Tvind’s facilities.

There are 457 social education facilities in Denmark. 35 of them, or 7.7 percent, belong to Tvind.

The municipalities’ total expenses for placements at such establishments amount to 2.3 billion kroner [$339 million]. Of them, Tvind’s programmes receive 114 million kroner [$17 million], or 4.9 percent.

Stability and fixed prices

But despite opposition from both the parliament and municipal politicians, Tvind has become the country’s largest player in the social education market. So what makes the municipalities send more money and more youngsters to Tvind?

In the municipality of Vordingborg, children and family director Annika Hermansen emphasizes that it is a coincidence when 30 percent of the municipality’s placements reside at Tvind’s treatment schools. However, the municipality has particularly good experiences with [Tvind’s] Bollerskov residence at Horsens:

“When the municipality chooses accommodation, we follow the applicable legislation which states that the municipalities must make use of facilities approved by one of the country’s five regional Departments of Social Supervision listed on the Offers Portal. Then we look at whether the specific programme is also right for the youths,” she says.

When the municipality specifically makes use of individual programmes, according to Hermansen, among other things, the municipality experiences stability in the fees charged by the facility, and the facility is consistent in its operations.

In other words, [the facilities that Vordingborg chooses] don’t give up on the individual child, and they do not suddenly charge additional fees, as Vordingborg finds that some other facilities, both private and public, can do:

“We have some experience with both residential treatment schools and municipal and regional day programmes, which after a year’s placement require more money for the task. And after the Child’s Reform [Initiative] was introduced [in Denmark in 2011], we cannot just move that kid if we are unhappy with the price. It must not only be economic conditions underlying a move,” says Hermansen, elaborating:

“At Bollerskov and other treatment schools, we find that prices are stable, although the task of handling the young person may sometimes be greater than it was at the start of the placement. For example, if the youngster escapes and must be collected at night, an added charge may be assessed. It is always the match between the specific child or adolescent and the programme that are the determining factors for the choice of a specific programme.”

In 2015, 22 out of 83 children and young people in the municipality of Aarhus had been residing at Tvind. Here, Erik Kastrup-Hansen, Director of Social Affairs, states that the municipality’s case managers choose the best suitable programme for the specific child.

“Also, based on what we believe will have the most effect and what the price is,” he says.

This article was produced in collaboration with the DBC.

Translated by TvindAlert.com

How we did it

To get an overview of the municipal expenses for Tvind’s residential treatment schools, kommunen.dk and DR have sought access to all Danish municipalities regarding how many children they have placed over a five-year period at various institutions, and how much money the municipalities have paid for the individual services.

These include a number of residences, as well as boarding schools, colleges and special needs schools.

The municipalities have entered data in a pre-produced form themselves, and it is this data that kommunen.dk has based its research on.

The places of residence that kommunen.dk and The DBC have investigated appeared in April 2017 on the website Tvindportalen.dk.

All municipalities have responded to The DBC's and kommunen.dk's request for information.

Tekst, grafik, billeder, lyd og andet indhold på dette website er beskyttet efter lov om ophavsret. DK Medier forbeholder sig alle rettigheder til indholdet, herunder retten til at udnytte indholdet med henblik på tekst- og datamining, jf. ophavsretslovens § 11 b og DSM-direktivets artikel 4.

Kunder med IP-aftale/Storkundeaftaler må kun dele Kommunen.dks artikler internet til brug for behandling af konkrete sager. Ved deling af konkrete sager forstås journalisering, arkivering eller lignende.

Kunder med personligt abonnement/login må ikke dele Kommunen.dks artikler med personer, der ikke selv har et personligt abonnement på kommunen.dk

Afvigelse af ovenstående kræver skriftlig tilsagn fra det pågældende medie.